Trib. UE 6 settembre 2023 , T-576/22, Bora creation slk c. EUIPO-Truie Skincare:

Marchio posterioore: denouinativo TRUE SKIN

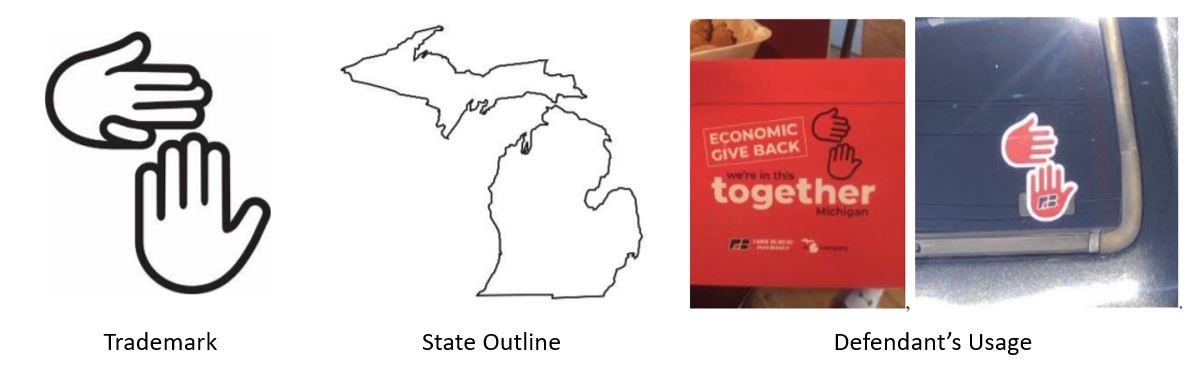

Marchio anteriore:

Classe 3: make up e simili

Rifl soggettivO: consumatore spagnolo.

Il trib. conerma che non c’è rischio di confuisione

<<69 A global assessment of the likelihood of confusion implies some interdependence between the factors taken into account and, in particular, between the similarity of the trade marks and that of the goods or services covered. Accordingly, a low degree of similarity between those goods or services may be offset by a high degree of similarity between the marks, and vice versa (judgments of 29 September 1998, Canon, C‑39/97, EU:C:1998:442, paragraph 17, and of 14 December 2006, VENADO with frame and others, T‑81/03, T‑82/03 and T‑103/03, EU:T:2006:397, paragraph 74).

70 In the present case, the Board of Appeal concluded that, in the light of the identity of the goods at issue, the average degree of inherent distinctiveness of the earlier mark, the below-average degree of visual similarity and the average degree of phonetic similarity of the signs at issue as well as the finding that the conceptual comparison remained neutral or that there were no relevant conceptual differences that could help to distinguish between the signs at issue, there was a likelihood of confusion on the part of the Spanish-speaking public which did not understand English, the level of attention of which was average.

71 In that regard, first, the applicant submits that the earlier mark is not essentially perceived as the word mark ‘true’, but that it is the figurative representation of that mark which makes it distinctive because, if that were not the case, that mark could not have been registered on account of the descriptiveness of the term ‘true’ for the English-speaking public. However, it must be pointed out that that argument is similar to that set out in paragraph 46 above and must therefore, for the reasons already stated in that paragraph, be rejected.

72 Secondly, as regards the conceptual comparison, which the Board of Appeal incorrectly found to be neutral, whereas the signs at issue are conceptually different, it must be held that that error of assessment does not have any consequences in the context of the analysis of the likelihood of confusion. As the Board of Appeal pointed out and as the Court has held in paragraph 67 above, the concept is conveyed by one of the two word elements in the mark applied for, namely the element ‘skin’, which is understood as referring to the skin and which is, at best, weakly distinctive with regard to the goods at issue, with the result that the conceptual dissimilarity cannot counteract the overall similarity between the signs at issue.

73 Consequently, in spite of the error of assessment which was made as regards the conceptual comparison of the signs at issue and although there are certain differences between those signs, it must be held that, following a global assessment, the Board of Appeal was right in finding that there was a likelihood of confusion, within the meaning of Article 8(1)(b) of Regulation 2017/1001, on the part of the relevant public>>.