Le piattaforme quasi sempre , quando convenute, eccepiscono la clausola di arbitrato stipulata on line tramite i terms of service TOS, in cui è inserita.

In questo caso il distretto nord della California, S. Josè division, 16 dicembre 2022, Case No. 22-cv-02638-BLF, Houtchens e altri c. Google, affronta il tema del se sia stata o no validamente conclusa la clausola di arbitrato col metodo c.d. clickwrap agreement per l’apertura di un account Fitbit (di proprietà di Google).

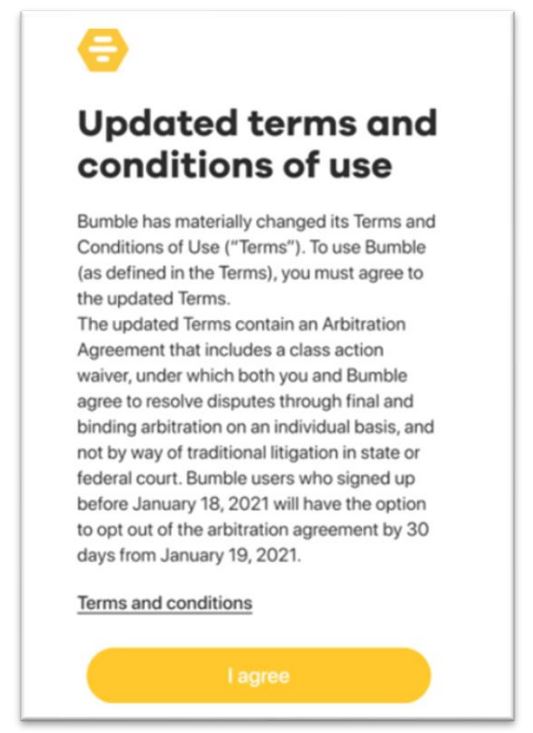

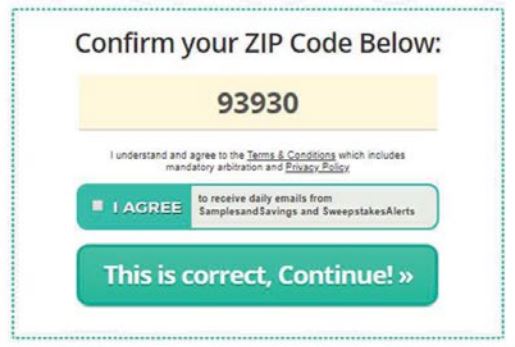

Si vedano in sentenza le quattro schermate a seconda del dispositivo (pc, cell. etc): in breve, si deve cliccare per i TOS su un quadratino che ad essi rinvia tramite link, e in essi pure alla clausola di arbitrato.

Per la corte, l’accordo si è validamente formato:

<<The Court finds that the hyperlinks to Fitbit’s Terms of Service in each of the above screens provided Plaintiffs “reasonably conspicuous notice” of the terms. See Berman v. Freedom Fin. Network, LLC, 30 F.4th 849, 856 (9th Cir. 2022). In the first three screens, the hyperlinks to Fitbit’s Terms of Service are presented in blue text in a sentence that otherwise uses gray text; they are next to the box a user must select to accept the terms; and the screens on which they appear are uncluttered. Court’s have routinely found that such a presentation supplies reasonably conspicuous notice of hyperlinked terms. See, e.g., Adibzadeh, 2021 WL 4440313, at *6 (reasonably conspicuous notice provided “where users must agree to the website’s terms and conditions before they can proceed, and the terms and conditions are offset in a blue text, hyperlinked text”). In the final screen, the hyperlinks are again presented next to the box that a user must select to accept the terms and the screen on which they appear is uncluttered; but instead of using blue font to distinguish the hyperlinks from the surrounding text, the page uses boldunderlined font. The Court finds that this page, too, provides reasonably conspicuous notice of the terms to which a consumer will be bound. Cf. Nguyen, 763 F.3d at 1177 (“The conspicuousness and placement of the ‘Terms of Use’ hyperlink, other notices given to users of the terms of use, and the website’s general design all contribute to whether a reasonably prudent user would have inquiry notice of a browsewrap agreement.”)>>